Antarctic ecosystem

Krill (Euphausia superba)

Demographic Reconstruction of Antarctic Fur Seals Supports the Krill Surplus Hypothesis

Summary

Scientists used advanced DNA sequencing (RAD sequencing) and population modeling to trace the genetic history of Antarctic fur seals at South Georgia Island, aiming to test whether increased krill availability led to larger seal populations. Their analysis uncovered a dramatic population crash during the commercial sealing era of the 18th and 19th centuries, when hunters nearly drove the species to extinction. However, the seals subsequently recovered to even greater numbers than before.The key finding was that the effective population size after the sealing period was roughly double what it had been historically. This supports the "krill surplus hypothesis" – the idea that industrial whaling removed so many krill-eating whales that it left more krill available for other marine predators like seals. With this abundant food source, seal populations were able to grow beyond their original size.

1

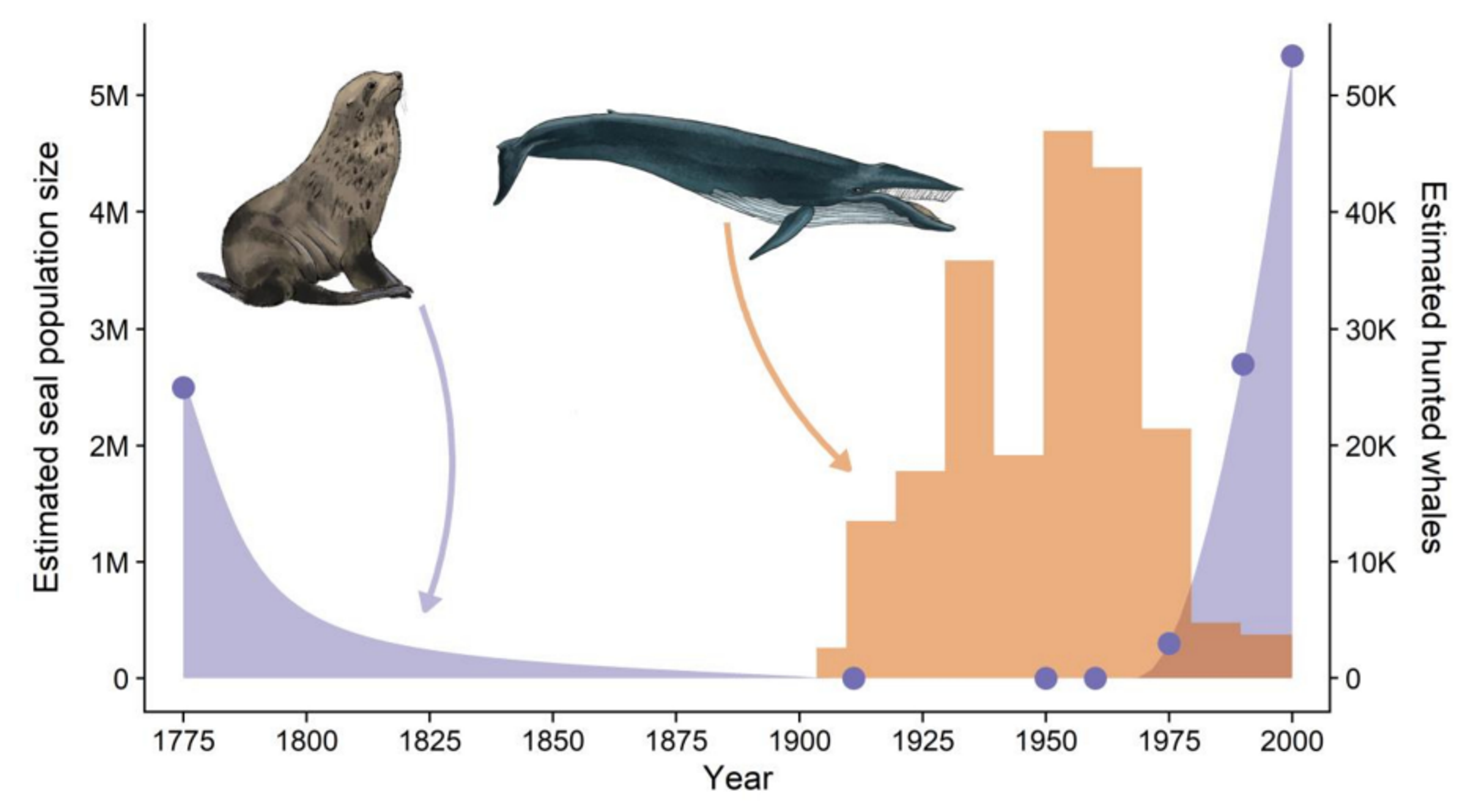

This graph shows temporal trends in Antarctic fur seal abundance and baleen whale harvesting. Fur seals were heavily hunted in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and were considered virtually extinct by the early 1900s. The seal population then experienced explosive growth during the second half of the 20th century, coinciding with baleen whale harvesting. Purple dots show fur seal abundance from empirical population estimates in the scientific literature. Whale data represents numbers of harvested baleen whales. Comparable whale population estimates from the same period are not available. We cannot show temporal changes in harvested seals because while sealing vessel records exist, the number of seals taken was often not recorded.Key Findings

1

The genetic data showed that during the sealing period, the breeding population dropped to approximately 534 individuals. This was a severe population bottleneck that nearly caused extinction. 2

After sealing ended, the effective breeding population grew to about 29,319 individuals. This was roughly twice the size of the original pre-sealing population of around 12,506 individuals. 3

This study provided the first DNA-based evidence that removing whales from the ecosystem created more food for other marine predators. The extra krill allowed seals to thrive beyond their natural capacity. 4

The research demonstrated that analyzing population genetics can effectively test ecological theories. It showed how genetics can help us understand how ecosystems respond to human impacts.