Fisheries management

Antarctic ecosystem

Climate

Krill (Euphausia superba)

Spatiotemporal Overlap of Baleen Whales and Krill Fisheries in the Western Antarctic Peninsula Region

Summary

This study examined when and where humpback and minke whales encounter krill fishing operations in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Researchers tracked 58 humpback whales and 19 minke whales between 2012-2018 using satellite tags, then compared their movements with fishing boat activity and catch records from 2015-2020.Using spatial random forest models, the team mapped where whales forage each month and found substantial overlap with fishing areas, particularly in the Bransfield Strait. Both whales and fishing vessels followed similar seasonal patterns, moving toward coastal waters as the season progressed. The highest overlap occurred in April-May when fishing effort peaked. Throughout the season, humpback whales increasingly concentrated in the Bransfield Strait, while minke whales stayed closer to shore in more limited areas.The findings reveal a critical management problem: current fishing regulations operate across massive areas (658,730 km² Subareas), but whales and fishing boats actually interact in much smaller zones spanning just tens of kilometers. This mismatch means existing protections may be inadequate.The research emphasizes the urgent need for smaller-scale, seasonally adjusted management strategies that respond to the changing patterns of both whale foraging and fishing activities. This becomes increasingly important as whale populations continue recovering and fishing operations expand in Antarctic waters.

1

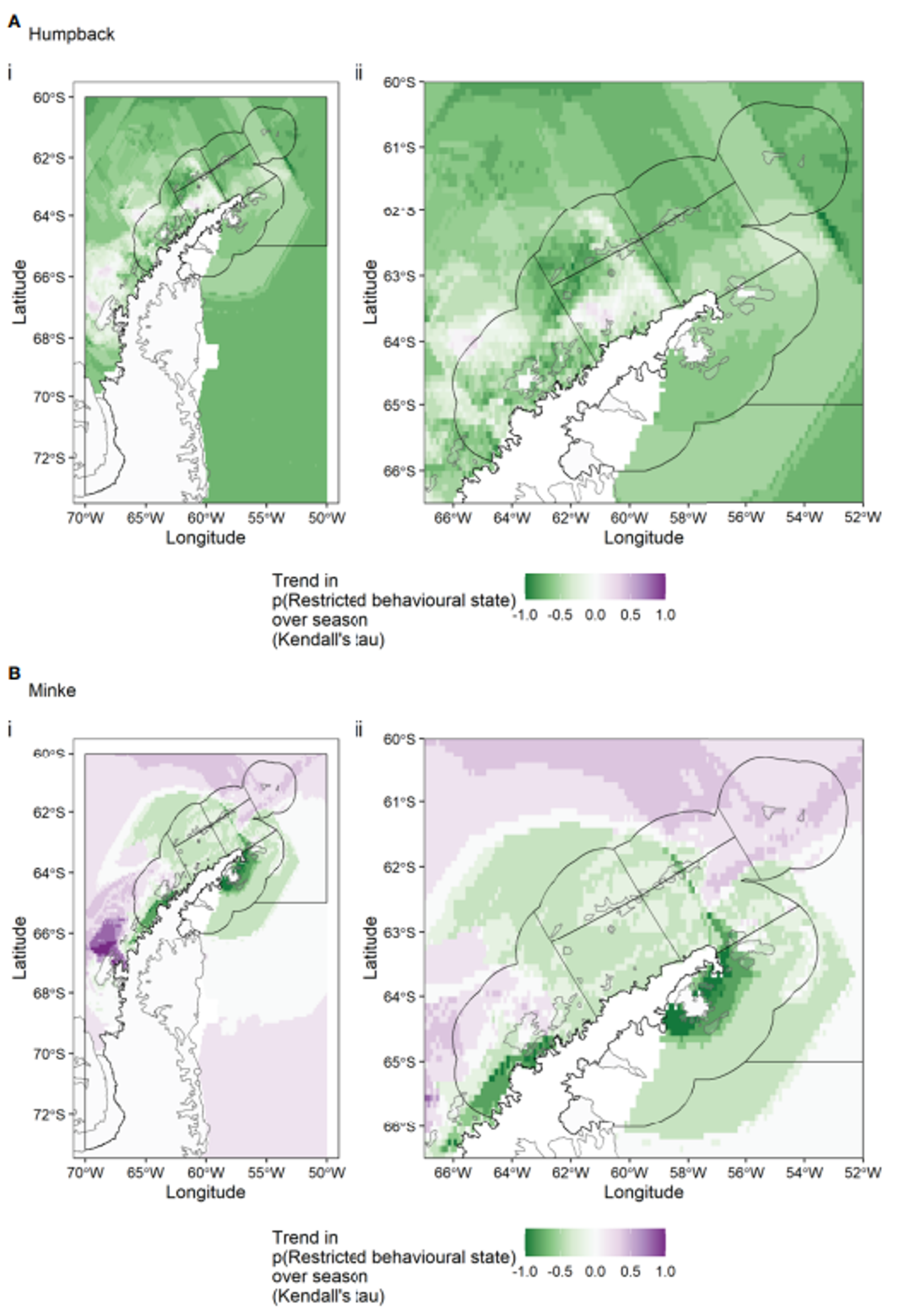

For humpback whales (A) and minke whales (B), this shows how whale behavior changed throughout the season. Green areas indicate where whales became less likely to stay in one place for feeding as the season progressed, while other colors show where whales became more likely to concentrate their feeding activities.Key Findings

1

Peak whale-fishery overlap occurs in April-May in the Bransfield Strait, where fishing effort and catches reach their highest intensity.2

Humpback whales increasingly concentrate in the Bransfield Strait throughout the season, mirroring the spatial patterns of fishing vessels.3

Minke whales prefer nearshore bays and sea ice areas, displaying different habitat preferences than humpback whales.4

Current CCAMLR management covers massive areas (658,730 km²) while actual whale-fishery interactions occur at much smaller scales of tens of kilometers.5

Both whales and fisheries move southwest toward inshore waters as summer progresses.6

Voluntary Buffer Zones around penguin colonies protect ~74,160 km² of area that also benefits baleen whales.7

Sea surface temperature drives humpback distribution while sea ice presence determines minke whale locations.