Biomass

Fisheries management

Antarctic ecosystem

Climate

Krill (Euphausia superba)

Stepping stones towards Antarctica: Switch to southern spawning grounds explains an abrupt range shift in krill

Summary

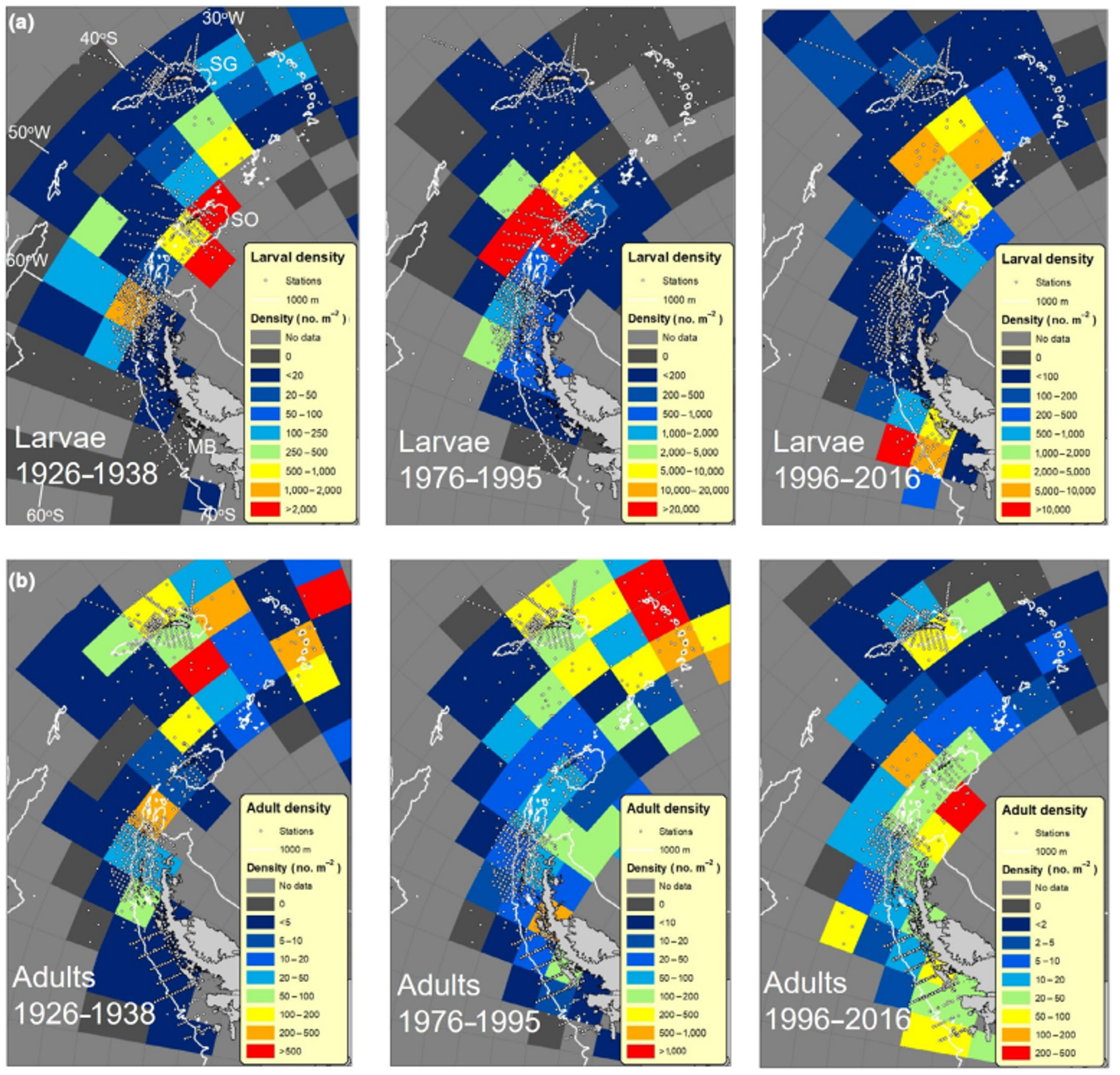

Antarctic krill showed an unexpected range shift of approximately 1000 kilometers southwestward during the 1990s-2010s. This occurred during a period when surface ocean warming had slowed, rather than during the preceding 70 years of rapid warming. This sudden shift was driven by changes in breeding success at different locations rather than simply following temperature changes. The Southern Annular Mode (a major climate pattern) became increasingly positive, reducing reproductive success in the traditional northern breeding grounds around the Scotia Arc while new southern breeding areas near the Western Antarctic Peninsula became established. This mechanism of sequential "stepping stone" breeding areas explains how polar species can achieve rapid range shifts that are disconnected from surface warming trends, with major implications for predicting future species distributions and planning marine protected areas.

1

Maps showing changing distributions of (a) krill larvae and (b) adult krill over the last 90 years. Note the different color scales, which were chosen to highlight the main population centers (bright colors) in each time period. This approach masks major changes in overall population density between eras, which are better shown in Figure 5. Dots represent sampling locations in each era. Coordinates are shown on the top left map, with regional abbreviations: MB (Marguerite Bay), SG (South Georgia), SO (South Orkney Islands).Key Findings

1

Krill shifted ~1000 kilometers southwestward during a warming hiatus (1990s-2010s), not during 70 years of prior rapid warming when distribution centers remained stable despite 0.5-1.0°C ocean warming.2

The Southern Annular Mode became increasingly positive, reducing larval feeding success and reproductive success in traditional Scotia Arc breeding grounds rather than direct temperature effects driving the shift.3

A new southern breeding area became established along the Western Antarctic Peninsula, enabling range shifts through sequential spawning hotspots rather than continuous population movement.4

The range shift occurred at ~500 kilometers per decade, which was faster than most observed migration rates for marine species.5

This mechanism shows polar species can achieve rapid range shifts disconnected from surface warming trends, challenging conventional climate-based distribution models and requiring new approaches for marine protected area planning.